The British Transport Museums

Introduction

In Part 1, I described the origin of the LNER’s railway museum in York. Until well after World War 2 this was the only railway museum in the UK, although there were several other museums that included railway exhibits and a great deal of smaller material in private hands.

This article describes how railway collections were expanded and managed following railway nationalization in 1948 and takes us to the point where circumstances changed and British Railways lobbied strongly to divest itself of the responsibility.

Please note that some additions have been made to Part 1 since it was originally posted.

Preservation Policy

In 1948, inland transport was nationalized and the railways, canals, London Transport and numerous interests in bus and freight companies passed to the British Transport Commission (BTC). The best that might be said of the BTC is that it was well-intentioned. Even before it took office in 1948 it acknowledged it had inherited a great number of old documents and physical artefacts and that there should be some mechanism for looking after them. Of course, the existing material would inevitably be supplemented by retiring locomotives, rolling stock and equipment that would also deserved a place in history. This would add to the bulk of the material and early action was suggested to establish some kind of framework to identify and retain whatever was appropriate.

The matter was gone into by the former secretary of the LMSR, Mr G.R. Smith, in 1949. Already the BTC was speaking about a possible museum, for which Smith was initially tipped as curator, anticipating the need for such an establishment before any of the background work had been done. Curiously, Smith was never actually transferred to the staff of the BTC and remained associated with the LMSR which, for technical reasons, could not quickly be wound up. This was not entirely without good fortunate as there was rapid retraction from the idea of appointing a museum curator in the absence of any kind of plan and he was simply asked to review the matter of preserving existing and additional transport relics and records and to report. It was agreed he would do this in his personal capacity given his knowledge of the industry and to pay him 1000 guineas (which was quite a lot of money in those days). Unfortunately when the report appeared, several of those asking for it felt that it was not of a very high quality. In fact one senior member of the BTC described Smith as ‘an unimaginative bureaucrat, quite out of his depth once away from the detail in which his life had presumably been immersed.’ For the BTC to accuse someone as ‘bureaucratic’ was damnation itself! It was in fact slightly unfair as some good points had been raised, nevertheless it was convenient to avoid further detaining his departure from the scene. Instead, a committee of senior officers and staff was established to produce some kind of policy, and this appeared in 1951.

The BTC committee was headed by Sidney Taylor (Deputy Secretary BTC), assisted by Christian Barman (BTC Publicity Officer, an ex GWR man with an interest in architecture and railway history). From the executives were J.R. Hind (Railways), H.F. Hutchison (London Transport), S.C. Howard (Docks and Inland Waterways), and T.H. Baker (Hotels). Smith gets a brief mention and is congratulated for his index of all the relics he had been able to find, suggesting the BTC’s thousand guineas had not been entirely wasted, though his activities were not referred to again.

Broadly the report confirmed that the existing railway museum in York would be retained by the BTC, together with another collection in Edinburgh. Additionally, the emerging collection of small exhibits identified by the BTC would be brought together in the shareholders’ room at Euston (and perhaps elsewhere) where they could be viewed. The whole mass of material needed to be catalogued, the larger exhibits preferably brought together for safe keeping and a curator for them needed to be appointed.

Broadly the report confirmed that the existing railway museum in York would be retained by the BTC, together with another collection in Edinburgh. Additionally, the emerging collection of small exhibits identified by the BTC would be brought together in the shareholders’ room at Euston (and perhaps elsewhere) where they could be viewed. The whole mass of material needed to be catalogued, the larger exhibits preferably brought together for safe keeping and a curator for them needed to be appointed.

In the longer term it was felt that a British Transport Museum in the London area should be provided, preferably in former railway premises, and the idea of using Nine Elms goods depot was floated. This had been built by Sir William Tite (of Royal Exchange fame) as the terminus of the London & Southampton Railway. The station went out of passenger use in 1848 but the frontage was intact and the old platform area and train shed remained largely unscathed as goods shed ‘B’. Immediate progress was impossible in the economic climate. I should add that when the matter was later reviewed, the Southern Region refused to release the site, which was still in use, and when it eventually became redundant the main block was demolished almost immediately in 1963 and the shed behind shortly afterwards. Those days were not good for the preservation of important buildings.

The inside of the shed at Nine Elms that was suggested for use as a museum

The report also referred to the great inventory of historic buildings. Many had survived in a meaningful form, but largely as a result of a combination of accident, fine construction and a continuation of their original purpose. Any building unhappily failing even one of these tests, if not already lost or mutilated beyond recovery, was an endangered species that could be lost without reference to anyone as soon as circumstances invited removal, or simply decay through neglect. It was felt that a preservation policy ought to apply equally to buildings. In fact this was not pursued as part of the quest to sort out non-property relics and building preservation was only recognized as important some decades later (by which time, of course, further buildings had been lost).

Implementing a Policy

At the time of the 1951 report there was mounting pressure from specialist transport societies for the BTC (a public corporation) to preserve important items for the nation. The idea of a British Transport Museum, ‘near London’, was therefore welcomed for presenting a coherent history of ‘British Transport’ using objects not better suited for display ‘in their respective localities’ (in other words the regional railway museums such as York). In 1951 the commission retained the services of professional specialists to take responsibility for records and for relics and Mr John Scholes was appointed curator of relics. Scholes had first become involved with museums in Southport and became curator of Southport’s Churchtown Botanic Gardens museum before WW2, and for a short while afterwards. He was then appointed curator of York’s Castle Museum, whose improvement and expansion he was responsible for. His task at the BTC was more demanding as there was no museum but there were vast numbers of relics. With few staff, no real idea of what had already been put on one side (or where) and no clear vision of what was expected, the task was somewhat daunting.

It will be seen from what had already been said that the BTC had inherited a great deal of historical material already. Scholes, its new curator, was assisted by ‘a small staff’, but progress was difficult against the BTC’s mounting financial losses and the absence of any specific legislation requiring the organization to maintain, and make available to the public, historic records and relics. Effort went into identifying and cataloguing the existing material. By the end of 1952 some 10,000 objects had been catalogued and donations of new material accepted from private individuals. The BTC knew it had a problem with display space but supported a policy whereby high-quality models of locomotives and other items might be made by apprentice engineers as part of their training, as these could be displayed a great deal more easily than a full-scale machine. The Commission already had quite a few exquisite models and the continued desire to accept representative models is one reason why the national collection now has so many of them (though the Science Museum, for similar reasons, also acquired many models for display).

One of the (seemingly) hundreds of railway models now held in the national collection. They are almost all superb models: surely they must be harder to make than the real thing because the work is so fiddly. They are an under-used resource now but when made were a practical alternative to full-sized objects for which there was no space.

In the meantime Scholes established an office initially at Euston and then at Fielden House in Westminster, a building used by the wartime railway executive and close to 55 Broadway, then the BTC’s headquarters. It was a couple of miles distant from the beating heart of practical activity at 222 Marylebone Road, where several BTC executives were based, including the Railway Executive (or ‘British Railways’, as it called itself). An early move was to begin assembling the smaller relics together in London and made arrangements to display them in a series of exhibitions in the shareholders room. The first was ‘London on Wheels’, in May 1953, in which year a mobile exhibition was arranged called ‘Royal Journey’, which comprised a number of royal vehicles that were displayed first in London and then visited a number of other towns and cities, attracting 154,143 visitors during the 80 exhibition days.

Two further London exhibitions were held at Euston; ‘Popular Carriage’ in 1954 and ‘Steam Locomotive: A Valedictory Exhibition’ in 1955. In each case a small charge was made for entry and the exhibition documentation was used as the basis for booklets of the same name that were available for several years. ‘London on Wheels’, was written by C Hamilton Ellis with a forward by Lord Hurcomb and a short section about the shareholder’s room itself which is unattributed but probably written by Scholes, who was responsible for its restoration. ‘Royal Trains’ and the ‘Popular Carriage’ were by C Hamilton Ellis and O.S. Nock wrote the ‘Steam Locomotive’ (this was subtitled ‘A Retrospective of the Work of Eight Great Locomotive Engineers’). The books were at least in part anchored to the material being accumulated in the BTC collection and even today are a readable contribution to the general knowledge about transport and were a useful addition to transport knowledge at that time.

The special exhibition train used for the Royal Journey mobile exhibition

In November 1956 a more general exhibition was opened at Euston, called ‘Transport Treasures’. This was a long term exhibition and it was regularly refreshed by changing some of the objects as only a small proportion could be displayed at any one time. It was arguably London’s first transport museum, though was confined to relatively small exhibits, including models. After great obstacles had been overcome, a mobile (train-borne) version was created and first opened its doors at Belgrave Road station in Leicester in June 1957 in conjunction with Leicester’s railway centenary exhibition. It was possible sometimes to include restored vehicles and locomotives, not previously having been on display, and at Leicester two locomotives and a dining car were included. The train visited many parts of England before heavy maintenance costs made continuance impossible.

Part of the London on Wheels exhibition in the shareholders room at Euston station in 1953. The showcases and other display apparatus were purchased with eventual use in a permanent museum in mind.

Against this increasingly challenging background the objective of establishing a Museum of British Transport somewhere in London (and regional museums elsewhere) had not altered. Arguably the regional museum at York already existed, even if it needed overhaul. A GWR Museum was sought at Swindon and a Welsh museum was mooted for Cardiff. A certain amount of Scottish material was already stored in Edinburgh, some of it on display. There was little manpower, little money and an awkward relationship with government as railway losses mounted and the modernization programme was not going well. Meanwhile the exhibits were piling up and desperately needed safe and secure storage facilities reducing risk of theft, accident and atmospheric deterioration. Scholes and his staff were collecting, restoring, conserving and displaying items and found themselves also providing advice to a huge range of bodies from Universities to local authorities, personal researchers, television and film companies and the BTC itself.

Examples of the exhibition booklets originally produced in 1953-6 for Scholes’s temporary exhibitions and remaining in print (with updated covers) until the late 1960s. They are published (top L-R) 1953, 1953 and 1954 (below L-R) 1955 and 1956.

The Clapham Museum

Towards the end of 1958 a disused bus garage at Clapham (formerly a tram depot) became available and Scholes felt that it could probably be made suitable at modest cost for conversion into the London museum. The decision weighed up cost of adapting the building, the imperative for finding homes for vehicles and other material already acquired, which had become urgent, and the probability of another site appearing that would be both better and remain affordable. He appreciated from the start that lack of rail connection was a hindrance but we should not overlook the fact that the BTC at that time owned heavy haulage contractors such as Pickfords and the railway depot at Nine Elms was not far away. The display space was 55,000 sq ft which, in the light of prevailing knowledge, was thought sufficient and there was also space for a reserve collection and 25,000 sq ft for offices, workshops and display galleries. Most importantly it had a vast roof with no supporting columns. It was mooted at the time that a large exhibit really needed 1000 sq ft of space to be able to view it properly, if that gives a feel for where things were heading. We might reasonably surmise the total floor area at Clapham (some on more than one level) did not exceed 125,000 sq ft but Scholes knew that if one included car parks, cafes, workshops and stored materials, lecture theatres and so on for the whole of the existing British collection, as well as sufficient room for expansion, then perhaps 60 acres might be needed, say 2.5 million sq ft. One has to include the regional museums in all this and even if there were six of them the same size as Clapham then there was going to be less than half the space available compared with that ideally needed. Fortunately the Clapham site hardly needed a car park (it had a very small one) but it was awkward for (say) coach parties. But it was a start, and for the reasons given the decision was made and matters unfolded accordingly.

The main hall at Clapham Museum early in 1961 whilst still being arranged. It is clear from the photo how useful it was to have no roof columns, which would have greatly constrained the layout.

The small exhibits were made available to the public from 29 March 1961 and this was fairly straightforward as it was an enlargement of the existing Transport Treasures displays. The larger exhibits in the main part of the building were at first available by appointment only and were only opened to the public from 28 May 1963. During that year 100,000 people visited Clapham (not fully open for six months), about 200,000 visited York and 250,000 visited the Swindon museum, which opened in June 1962. One might observe that all three museums now levied an entrance charge and I draw attention to the irony (noted at the time) of the facilities having been free under private ownership and charged for under public control!!

The flyer designed to encourage people to visit the new museum when only the small exhibits section was open and access was from the rear of the building.

The small exhibits section at Clapham, opened in 1961. The showcases appear to be those previously employed in the Shareholders room at Euston.

The museum at Clapham was well received and the large hall contained a number of main line locomotives, carriages and other equipment and buses, trams, railway rolling stock and other material that London Transport had been storing for some years. There were a few exhibits from the BTC’s wider activities too. There were extensive displays of small exhibits, posters and publicity as well as the large material. I visited frequently as a schoolboy and found the place captivating. Scholes explained when the museum opened that he had managed to include over a hundred (mainly) rail and road vehicles covering 125 years of history. Mostly vehicles were in ‘original’ livery (I’m not going to debate that) but the purpose was to show off the wealth of craftsmanship and the story of an industry which was famous throughout the world. It should not be thought there were only vehicles and the small exhibits for there was also a good deal of other railway paraphernalia to be seen. Most people who saw the museum at the time were very complimentary about it. Ian Nairn, who was not the most easily pleased of critics of social architecture, covered it in his 1966 book, Nairn’s London, a sought-after work recently reprinted. He was positively enthusiastic about it, or more particularly its contents. The historian Jack Simmons had studied transport museums and he too had much good to say about Clapham. Something had gone right!

The main entrance to the Museum of British Transport in Clapham High Street in 1963-4, the culmination of nearly 70 years of agitation for a national transport museum. I do not think the Rocket display outside was there on opening day, though it appeared shortly afterwards. It is a replica (one of nine!) and the original is in the Science Museum. The replica appears to have been one made by the London & North Western Railway in 1881 (or 1886) as a static display. After Clapham closed the woodwork was found rotten but the frames and some other parts were recovered and used to make a steaming replica (built 1975-79), now kept at York. The building extended all the way back to Triangle Place (which was the staff entrance and postal address, and used to access the small exhibits before the main hall opened). © National Railway Museum and SSPL

Clapham at first included a number of waterways exhibits, some of which were problematical when not displayed in the context of water. When at about the time of Clapham’s full opening the British Waterways Board developed its own museum at Stoke Bruern, Scholes was pleased to pass across the waterways exhibits. It was better they be all in one place (which was also on a canalside) than try to do the job badly in Clapham, and it released a small amount of additional space.

The opening of the new museum was a big event in London, and British Pathé covered it in one of their newsreels, which you can see HERE.

John Scholes entertaining some visitors

A representative view of part of the main hall at Clapham shortly after opening. To have all the exhibits finally on display like this was a triumph. The displays were hardly contextually arranged, though, and in many ways are comparable to those at the NRM York today. in that one has to fight for the story.

Another view of part of the Clapham display. On the right is another replica of the Rocket whilst in the foreground is an 1846 Furness Railway locomotive for many years displayed at Barrow and bearing the scars of a WW2 air raid.

Although the curatorial staff were BTC (and, later, British Railways) staff under Scholes’s control the security and ancillary staff were from London Transport, mainly staff medically retired from (typically) driving a train or a bus but otherwise fit. Once the main exhibits had been opened to the public the entry charge was increased to 2 shillings and 6 pence (weekdays only, though Sunday openings occasionally took place later and were popular).

The Swindon Museum

The Swindon museum had always been developed with the support and involvement of Swindon Corporation, which supplied the building. This had been designed and constructed by Brunel in the early 1850s for the GWR as a set of model lodgings for railway staff but not found popular. Subsequent conversion to self-contained flats proved equally problematic and around 1869 the company disposed of the building which became a Wesleyan chapel. The last service was held in September 1959. By happy coincidence the BTC was by then looking for a site for its GWR museum and the building was judged very suitable. With such use in mind, it was conveyed to Swindon Corporation in 1960. Use as a museum benefited both the corporation and the BTC, which was responsible for providing and arranging the exhibits and operating the facility, which, as already noted, opened on 28 June 1962. The ceremony was performed by R.F. Hanks, chairman of the BTC’s Western Region board in the presence of the Mayor of Swindon and the General Manger of the Western Region, Mr S.E. Raymond, who was soon to become BR chairman. In Hanks’s speech he mentioned he was an incurable railway sentimentalist. I don’t think we could say the same of Raymond, as we will see in due course, or of Beeching, who was Hank’s boss when he disclosed his inclinations!

The arrangements for management of the museum were perhaps over-complicated. During the setting up process the practical impetus was left in the hands of British Railways’ Western Region which at first carried the cost of restoring and preparing for exhibition many of the large exhibits at the nearby Swindon works; it also conducted the negotiations with Swindon Corporation. The actual selection of exhibits was made probably before the work on the museum began (and I think in London by Scholes, after the consultation process). The fitting out was undertaken by a team in Swindon led by R.H.N. Bryant, the staff assistant to the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Western Region and included staff familiar with moving large railway objects, including Pickfords. The actual movement of exhibits began on 18 March 1962. This position reflected the practical position that the railway regions had been given formal responsibility for preserving items of interest in 1958 and had the commercial and legal expertise in house. To an intriguing extent the railway regions carried on the practices and attitudes of the pre-1948 main line railways, the Western Region, in particular, regarded itself as a slightly updated GWR. In any event, the museum at Swindon was going to be a GWR museum of which the Western Region would be proud.

City of Truro being manoeuvred into the new museum at Swindon. This was not a simple job.

Regrettably the cost of leasing the building exceeded the estimates and the cost of preparing the exhibits exceeded estimates by three times the £7000 expected, the Western Region managing to pass these to BTC headquarters via Scholes’s office. After that, Western Region interest began worrying about more urgent matters and the museum management found itself in the hands of a ‘Great Western Railway Museum Swindon Joint Management Committee’. Upon this vital body sat two Swindon borough council members (with other staff in attendance), and four BTC (later British Rail) staff, including Scholes. Day to day management was in the hands of the borough librarian and curator, Mr Harold Jolliffe, and amongst the museum staff was one Neil Cossons who took up his duties on 3 December 1962 and who many years later found himself director of the Science Museum, to which we will turn in due course.

The entrance to the Swindon Museum, shortly after opening

This nice little booklet was produced to commemorate the opening event and the contents clearly show the complexity of installing a railway museum in the building.

As the prototype for the BTC’s regional museums, Swindon was probably as good as it gets. The theme was almost exclusively devoted to the Great Western Railway whose activities not only dominated the town but most of western England and Wales. A combination of impressive locomotives and a wide range of supporting exhibits (such as track) and what we would call small exhibits, was put together in a thoughtful way in an interesting building. It was a good way of getting stuff on display that would be harder to justify in a national collection and was relevant to the area, The famous railway author and preservation activist Tom Rolt was prevailed upon to write a rather nice introductory book about the GWR and the museum, published in 1963, and it explains the importance of the material contained therein. I treasure my copy! The historian Jack Simmons liked Swindon and, like me, was struck on entering an interesting building by the atmosphere which reeked ‘Great Western’ more than any book or photograph could do, or ten minutes on the draughty and run down station. There were only five main line locos at first but they were splendidly arranged. One of the locos was City of Truro which Hanks had first seen, looking a little out of place, in the York museum and which had now been repatriated ‘as she rested among her own kith and kin’. He hoped the museum would not only present something of the past glories of the GWR but also demonstrate the huge task today’s managers had in modernizing the system.

The Churchward Gallery at the Swindon Museum. Left image is the chapel as it had been. Right image is the same space after installation of track and locomotive exhibits.

It was not a large museum but was unable to cover its costs. Unusually this museum opened on Sunday afternoons as well as weekdays. The adult admission charge was one shilling and at some point (perhaps later) included admission to the nearby Railwayman’s Cottages. Swindon may be a good place for a company museum and for expressing the might of local industry but in those days it was hardly on the tourist trail. Despite valiant efforts from the Swindon staff it was impossible to improve visitor numbers. This will become important shortly.

The York Museum

Upon the formation of British Railways, when transport was nationalized in 1948, the museum at York was operated by the Chief Regional Officer of the North Eastern Region and a museum committee. Day-to-day management was still in the hands of curator, E.M. Bywell, who had been in post since 1922 (notwithstanding his other duties) but who had actually now retired and who still did the curating job voluntarily and without pay. I note that in the 1933 catalogue, LNER Chairman (William Whitelaw) thanks him for ten year’s work. Heaven knows how old he was when the BTC inherited him. At this time, admission was still free and the only source of income was from sale of the catalogues, at sixpence each (eightpence from 1951), some of the proceeds of which were used to acquire new material. The catalogue had been kept up to date and new editions appeared in 1947, 1950 and 1956, each reprinted as required. It appears that sometime after the appointment of Scholes the old regime was quietly eased out and evidence of a more modern approach began to appear. This coincided with the introduction of a small entry charge from April 1957 to help defray costs, which does not seem to have been anticipated when the 1956 catalogue was produced as a special slip had to be printed for insertion.

During 1958 the small exhibits section was temporarily closed for reorganization, reopening on 19 May. To commemorate this two royal vehicles were displayed next to the main section of the museum as an added attraction. These were normal stored at Wolverton, to where they returned when the exhibition closed on 27 May. Shortly afterwards some more persuasive publicity began to appear in order to increase the number of visitors, and a nice little brochure, entitled ‘The background story of the exhibits’ was written by historian and preservation champion Tom Rolt, which appeared in 1958.

On the left is the cover of Tom Rolt’s 1958 booklet about the York Museum. It is very much a narrative rather than a guide book. On the right is a contemporary leaflet (possibly slightly later). This is a rather nice promotional piece opening out into eight pictorial pages, then foldable vertically to make it pocket size.

During 1959 the York Railway Museum obtained the services of Bob Hunter as its own curator, though subordinate to Scholes in London. Hunter’s origins such as equipped him to take local responsibility at York are not known to the author but he was a leading light in the Festiniog railway society in his spare time and clearly had a deep interest in preserving past glories. We shall hear more of him in Part 3.

Although the general atmosphere at York remained substantially unchanged throughout the period of the BTC, there were changes to the displays. To the surprise of some, Great Northern loco Henry Oakley was borrowed from York in September 1953 to double-head with another loco stored at Doncaster two special trains from Kings Cross to Doncaster and Kings Cross to Leeds for commemorative trips organized by Alan Peglar (later to buy Flying Scotsman). Since Henry Oakley hadn’t steamed since 1937 and was very difficult to extricate from the museum because of the constricted layout, this was a major event. The loco was returned unscathed, with the upheaval repeated to get it back. In 1957 the even more difficult job was undertaken of extracting City of Truro. The immediate need was for it to haul a trainload of Festiniog Railway members on a special from Wolverhampton to Ruabon, requiring a great deal of preparation as this loco last steamed in 1931. This was not to return to York as it was foreign to those parts and was earmarked in due course for Swindon (as noted earlier). The space was quickly occupied by two more appropriate locos. I mention these lest the impression be given that the York museum was left untouched during the BTC period, for it was not. The emphasis was perhaps more closely focused on the north east, though curiously the City & South London coach remained at York even after Clapham opened, though the latter would have been far more appropriate as the coach once rumbled through the tunnels right in front of the museum.

Two 1950s leaflets for the York museum. On the left, while museum is under North Eastern Region control, it is branded British Railways. On the right, the 1956 version is branded British Transport Commission, perhaps reflecting the more intimate supervision from John Scholes’s department.

The museum maintained close links with the North Eastern Region although Scholes was firmly in charge of the exhibits and arrangements for display. At no time did the local council become involved in any way with the museum, unlike Swindon.

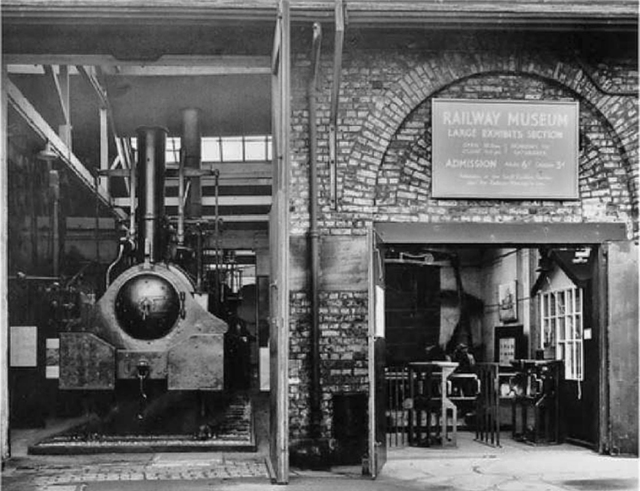

The entrance to the large exhibits section at York, probably about 1960.

I should add here that in parallel with the worries about relics, others were worrying about records. A BTC archives office had quickly been established near Paddington to which all redundant pre-1948 records were sent for indexing and safe-keeping but the monumental task was eased a few years later by setting up a branch office at York, in the basement of the former North Eastern Railway headquarters; this also included a small search room for researchers. At some point, I have not established a date, some of the York Museum paperwork that appeared more appropriately classed as an archive was transferred to the BTC archives at York. When, some years later, the BTC archives were transferred to the Public Record Office the York Archives were closed and the records were broken down, with duplicate material disposed of and unique material transferred to London. Certainly part of the Briggs collection followed this path and split what had been a coherent collection. Though this may not have mattered too much in this case I doubt if it was what the donor had expected. These Briggs documents can now be viewed in the national archives at Kew and it is very likely that other York Museum material came the same way.

The Railway Museum at York in 1958. On the whole it may fairly be said that little space in this 250ft long building was wasted.

The Glasgow Museum

I have mentioned the Edinburgh collection of material, which was also assembled by the LNER in respect of Scottish railways and which after 1948 fell into the Scottish Region, which also inherited the Scottish lines of the LMSR. The Edinburgh collection had been assembled gradually since 1938 by Lieut Col Murray (of the LNER), who was supportive in the 1951 discussions of there being a national museum in London but did not want to lose items of particular Scottish local interest. When inventory preparation was required it was found some items had gone missing (almost certainly a problem elsewhere, too). Nevertheless there was a desire for a Scottish regional museum.

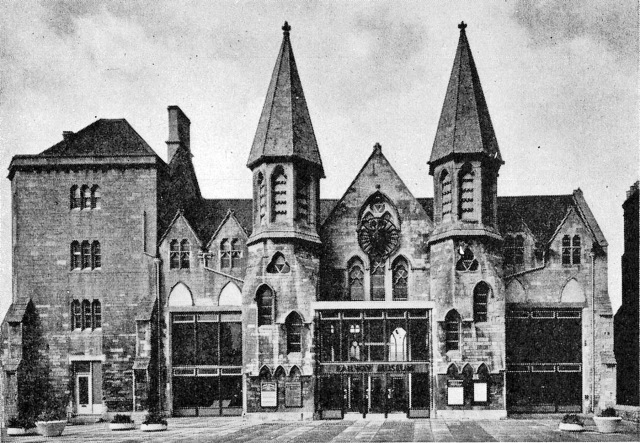

With support from Scholes the Scottish Region cast about for a permanent home for its Scottish transport material. It so happened that in 1958 the City of Glasgow announced it was to close its extensive tramway system and wanted to preserve and display a selection of representative vehicles and equipment. Glasgow’s existing Art Gallery and Museum at Kelvingrove already held transport material (including some large railway material) and it appeared sensible to establish a single transport museum. Fittingly the site selected for this was the redundant Coplawhill tram depot (in Glagow’s Pollockshields district). This appeared to be just the location the BTC was looking for as a home for the Scottish railway and associated relics and discussions led to an agreement to display between the two parties. Glasgow was felt particularly appropriate since the Scottish locomotives to be displayed were made there.

Glasgow was a general transport museum inspired by loss of the City’s tram system of which a number were preserved for display. Supported by the BTC as part of its regional railway museum policy, railway material relevant to Scotland was displayed and this shows part of he railway section.

The Glasgow Transport Museum was opened in part by the Queen Mother on 14 April 1964 when the tramway exhibits predominated. It was much-extended on 8 March 1967 when the railway locomotives went on display. It was a substantial transport collection, heavily reflecting local industry, and included six locomotives of local interest, one of them privately owned (and later withdrawn so that it could be put into working order). It is true that pride of place was given to the tramway vehicles, but at least the railway material was now displayed and was reasonably secure. The arrangement was much more heavily focused around the local authority than was Swindon or York and in 1966 the five BR locomotives (and I suppose all the other rail material) was transferred to Glasgow City ownership and was never part of what later became the national collection.

The Glasgow Museum of Transport in Pollockshields not long after it was established and before many public buildings were cleaned. It was actually quite near the City centre. Scottish Daily Record.

The museum moved to the exhibition building at Kelvin Hall in 1987 (this should not be confused with the nearby Kelvingrove museum—Kelvin Hall was a large exhibition space that had functioned rather like London’s Olympia or Earls Court but was looking for a more stable use). The problem with the old transport museum was that it was wholly unsuited for use as a long term museum, particularly on conservation grounds. Kelvin Hall provided a more stable atmosphere and had good facilities for moving large objects in and out. The vast collection of models of ships associated with Glasgow had already been amalgamated with the transport exhibits at Coplawhill in 1976 having previously been in the west wing of Kelvingrove and the unsuitability of its new surroundings quickly became evident.

Although Kelvin Hall was a much better location for a transport museum, the enthusiasm created by Glasgow’s selection as European City of Culture in 1994, coupled with the massive redevelopment of the Clyde waterfront, created a desire within Glasgow City Council for a purpose-built museum focused on Clyde industries and transport in particular. And so was born the Riverside Museum. The transport museum at Kelvin Hall was closed in April 2010, the collection being subsumed by the new museum which opened in 2011. The Riverside Museum has not been entirely without controversy but shows off a very wide range of exhibits in a more stable environment and with better facilities for visitors. However, it now drops away from our story, though it does one day deserve a review as there are presentational difficulties. The only point I want to make here is that one notes that in Scotland there was a feeling that ‘transport’ was a single entity worthy of a museum whilst in England matters were to go in a different direction with public displays divided by mode. Can both be right?

Two of the railway exhibits at Riverside, just to give a flavour. Much of the museum has a very high roof whilst floor area is still limited. The effect is mitigated by stacking objects above each other, even quite large objects. This is an interesting solution but can make viewing very difficult. In this image all is not as it seems as the upper loco is actually part of a display on the first floor!

The Other Regions

The North East Region, Western and Scottish regions were all on track for their own museums but there was less enthusiasm from the vast London Midland Region which eventually hinted that a roundhouse at Derby might be able to take the retained LMSR locomotives. The Eastern grasped the principle and was prepared to share a museum with another region but did not want to proceed on its own. This did not quite answer the directive which the BTC chairman (Sir Brian Robertson) had given for establishing regional museums but was accepted as a temporary position. (It wasn’t suggested they went in with the North Eastern but that would have been logical if extra space were found in York; the two regions were later merged anyway). The Southern seems to have had fewer relics and suggested their large exhibits would not form a museum by themselves (though it was pointedly observed by headquarters that there was already difficulty storing its existing retained locomotives). Without great enthusiasm from south of the River the matter seems to have been put to one side and was subsequently overtaken by events.

A Confusion of Activity

Even in the early days of the BTC its labyrinthine organization defeated the simplest of requests that items of historical importance should be retained. The contents of the royal waiting room at Windsor were auctioned off by the Western Region in September 1950 but the BTC itself only discovered this in July 1953; the chairman, Lord Hurcomb, was furious and wanted to know why the BTC had not been consulted. In 1952 a coach was destroyed at York after becoming infested with woodworm. By then Scholes was in place but had not been consulted; he felt that it could have been saved if he had been notified of the problem as soon as it was discovered. There was much the BTC had to learn. I must stress that the BTC in some form or another employed nearly 900,000 staff in 1951 and that getting even simple things done or changed was challenging.

As that decade progressed, John Scholes became increasingly involved in the day to day problems presented by the collections he had immediate control over, his temporary exhibitions and the massive job of finding a new museum site and then getting it up and running. By the late 1950s the total number of objects on inventory was approaching a million whilst the large exhibits were strewn around the country, sometimes in unsuitable conditions, with some being repaired or restored. This was quite a big job not made any easier by the BTC’s structure. The small BTC headquarters staff (now at Marylebone Road, and of which Scholes, still in Westminster, was a part) had policy control over the functional committees that controlled the various activities, by far the largest of which was British Railways. This truly vast organization was broken down into the six railway regions, with headquarters spread around the country. These were also vast and were broken down into smaller districts, and so on, which is was where all the knowledge was. The actual preserved exhibits were spread about in odd sheds where there was space, together with other redundant equipment and a very long way down the chain of command from those controlling preservation policy. The historical relics section was outside the railway organization altogether and had great difficulty exerting its will, let alone a policy, across the diverse and varyingly cooperative regions.

You will not be surprised that mistakes were made. In 1957 three exhibits stored at Stratford works were scrapped in error. They were a Wisbech & Upwell tramcar, a GER tram locomotive and an LTSR bogie third carriage, all irreplaceable. The tram engine was of the type that inspired the Rev W. Awdry’s tram ‘Toby’ whilst the tramcar (really a carriage) had been put on one side and survived long enough to appear in the film ‘The Titfield Thunderbolt’. The uproar this caused reached the desk of the BTC chairman, Sir Brian Robertson, and in consequence the processes were, at least in part, improved for identifying, scheduling and storing equipment and relics safely. As much part of the problem had been establishing whose job it was to identify what needed to be preserved in the first place, about which there were many differing points of view.

Another consequence of the scrapping was that the BTC’s chairman received a deputation from several specialist transport societies who were in some respects better acquainted than the BTC itself about the historical significance of material already stored or about to be retired. I say ‘in some respects’ because of course if one has a society devoted to one type of thing then it is unlikely to propose items for preservation that fall outside its remit. Certainly neither Sir Brian Robertson (nor probably Scholes) was desperately keen to arbitrate over some of the finer issues and it was suggested the societies themselves form a committee to go into all this and come up with a single set of recommendations about items for preservation that could be discussed with the BTC, and in particular with Scholes. So far as I can tell Scholes was always very supportive of this since it actually gave him better arguing power when dealing with the regions. And so was born the Consultative Panel for the Preservation of British Transport Relics.

The panel reviewed the whole of the existing collection, what was likely to become available shortly and where there appeared to be gaps. Scholes was always invited to Panel meetings and various approaches were discussed prior to the final recommendations being made. The Panel’s views did not necessarily accord with the transport press, who made various criticisms, nor were all the recommendations accepted by Scholes and the railway regions, but on the whole the consultative approach worked reasonably well and the final list of scheduled locomotives could be justified on various grounds. The story with carriages is I think rather less of a success story as effort was put (perhaps necessarily) into quite old material without much thought being given to the commonplace items inter-war, post war, or even current (given the modernization plan being rolled out and vast numbers of vehicles likely to be disposed of). Goods vehicles were rarely mentioned. Only after the locomotive saga had been put to bed did effort really turn to signalling, permanent way and other items. This was a bit patchy and really reflected the interests of the representative societies. There was a need for advice though, as by the mid-1960s vast amounts of equipment were coming out. The Panel continued to do useful work for a little longer but we shall see in the next part that with the museums fighting for their very survival, and uncertainty about what might replace them, discussions about some unusual signal rodding at (say) Loampit-on-the-Marsh was of interest to no-one!

What we do see during this period are the first ominous signs of troubles to come. The reasons are not new—to some, they were already very familiar—but they were new to the BTC. I offer below some of the ‘matters that weighed on the minds of those intimately involved, just to give flavour.

- Not everything can be kept.

- What subset of ‘everything’ should be kept, and why?

- —Who decides?

- What happens if more is kept than can be displayed?

- What subset of all that is kept should be displayed, and why?

- Who are expected to view the displays and why do we think this?

- Where is material to be displayed?

- Should it be operative or static?

- What weight is given to ‘what people want to see’, irrespective of an object’s historical significance?

- —Who decides?

- Who pays (and why)?

- Since there is little possibility that any group of rational people involved in these processes would all agree on all the points, how does one get a working long-term consensus?

- What counts as ‘success’?

- What measures are necessary to ensure all of this is done satisfactorily (or at all)?

I shall leave all these questions hanging because it is a theme I shall return to later. Suffice to say that the BTC had to work much of this out for itself whilst at the same time having inherited an existing museum and a great number of objects (with more on the way) and so was not entirely free to make decisions from first principles anyway! I have already noted that there were weaknesses in the ‘who decides’ and ‘how do you know it is being done’ areas. I shall merely hint here that of the rudimentary list of points above, I think the last point (possibly the last two) are the most important providing it is done in a supportive and professional way and does not degenerate into a tick-box culture operated by people entirely ignorant of the issues involved. I rather think that much of this had to be done by Scholes himself, without a great deal of support from an organization about to self-implode.

Conclusion

This section has examined the way the three (arguably four) British transport museums emerged from the hiatus of transport nationalization in 1948. For fifteen years there was a consistency of policy for a national ‘transport’ museum and regional museums where practicalities meant they would inevitably tend to focus on railways. Swindon was most blatantly a railway museum but Glasgow embraced with enthusiasm various other modes, though mainly from that locality. The policy was carried out not entirely from scratch, but those involved had a huge amount to learn along the way. By all accounts the resulting museums, from the view of those visiting them, were a very creditable achievement, the more so given the financial and other constraints that had to be contended with.

This did not last.

In the next part, I will explain what factors conspired to frustrate this direction of travel and how, after the battle of York, we ended up with a national railway museum. In the final (fourth) part I will make some observations (I hope objectively) about how that museum is doing nearly half a century later.

York Museum says “… after 1956 a small entry charge was introduced …” but the photo below headed “The entrance to the large exhibits section at York, probably about 1950” shows admission adult 6d child 3d.

LikeLike

Quite right – I was confusing it with catalogue price which was 6d in 1950. Will amend.

LikeLike